From the book "The Eye Expanded: Life and the Arts in Greco-Roman Antiquity", Frances B. Titchener and Richard F. Moorton, Jr., editors; chapter 16 “Macedonian Redux” by Eugene N. Borza, page 249-266, 1999.

Sixteen

Macedonia Redux

Eugene N. BorzaA nation is a group of people united by a common error about their ancestry and a common dislike of their neighbors.

ROBERT R. KING, Minorities under Communism

An essay on modem political culture in a volume devoted to reciprocity in life and art in the ancient world may require a word or two of explanation. The theme of what follows is the modem rebirth of ancient Macedonia as a symbol of nationalism in a part of the Balkans that has been a killing ground in recent times. Many contemporary observers have attempted to reinvent the ancient history of the region in order to fit the necessities of their own lives and the vagaries of modem Balkan politics. It is a distorted reflection of the past, which, in its warped form, serves a purpose useful beyond the romantic antiquarianism of the classroom, the tourist path, and the museum. Midst the great body of Peter Green’s scholarship on literature, art, and the history of antiquity, one must not lose sight of the fact that he is one of our most perceptive observers of modem Greece, having lived among Greeks for several years, and having understood them better, perhaps, than they might have wished. Green’s essays in publications such as the New York Review, the New Republic, and the Times Literary Supplement are a rich source of insight for anyone who not only wishes to know something about contemporary Greece, but also requires some understanding of the issue of continuity and discontinuity between the past and present. 1 I hope that he will accept this essay in the spirit he has expressed in his own work on like subjects.

In the spring of 1993 I taught an undergraduate senior seminar to History majors, the topic of which was “Ethnic Minorities and the Rise of National States in the Modem Balkans.” We examined the status of minorities following the founding of Serbia (1815), Greece (1832), Bulgaria (1878), Albania (1913), and Yugoslavia (1918). Not long into the semester I asked my American students to identify their own ethnic backgrounds. One young woman said proudly that she was “Macedonian.” Grist for my mill. I asked her what that meant: was she Greek or Slav? She answered that she was Macedonian, and certainly not Greek, although she pointed out that she had spent most of her school life pretending that she was Greek, for, whenever her teachers asked about her ethnic background and she answered “Macedonian,” they responded, ”Oh, you must be Greek.” Now, as an honors student and a senior at a major university, she had stopped pretending she was Greek, and took my seminar in part to help her learn something about her Slavic Macedonian background.

Her family lived near a decaying central Pennsylvania mill town called, appropriately, Steelton. About halfway through the semester, the student told me that she had visited her church cemetery in Steelton, and that she had seen a number of gravestones on which the deceased had been identified as having been born in “Macedonia.” I asked what the dates of burial were, and she said “Oh, the 1950s.” “Not good enough,” I responded, ”Next time you visit, look for earlier dates,” knowing that by the 1950s it would not be unusual for birthplaces to be given as “Macedonia” in light of the federal status of Macedonia as a Yugoslav Republic. About two weeks later my student informed me that she had seen gravestones of the 1930s with the Macedonian identification. I jumped at the chance. “I’m going to pay you a visit in Steelton,” I told her. “Find some old-timer in your church, and let’s go looking for gravestones.”

Steelton is located along the Susquehanna River, just south of Harrisburg. The deteriorated mills, now largely deserted, stretch along the river, separated from a dilapidated old working-class community by a highway. Affluence has lured many people into the suburbs of Harrisburg a few miles away, and the houses and people who remain have clearly seen better times. The town climbs a bluff from the river. The higher parts are marked by greenery, better kept and larger homes, and bits of parkland. On the summit of one of the highest bluffs is an open, grassy area of several acres, the site of the Baldwin cemetery. Within lie the remains of immigrants who escaped the violence and poverty of Balkan life generations ago to seek economic well-being in the mills of Steelton.

The old woman who accompanied us knew the history of the cemetery and the churches whose members were buried there. One of the first things that struck me was that, by and large, the deceased who were identified as Serbs, Bulgarians, or Macedonians were buried in separate parts of the cemetery. In death, they sought the separation that sometimes eluded them in life. The old Macedonian woman had little but contempt for the Serbs, many of whom she had known, but she sometimes appeared confused by the distinctions between Macedonians and Bulgarians. For until the establishment of the Macedonian Autocephalous Orthodox Church in 1967, 2 the Macedonians belonged to either the Bulgarian Orthodox Church or to the “Macedonian-Bulgarian” Orthodox Church described on a few gravestones. Indeed, the Macedonian community in Steelton had apparently experienced internal division over whether their priests should most legitimately have been trained in Macedonia or in Bulgaria.

We picked our way past hundreds of gravestones, stopping to take photographs 3 and looking for earlier dates. Some stones were engraved in Latin letters, most in Cyrillic. A few decrepit headstones had been replaced with new ones, but most were original, and I mused that my old teachers of epigraphy would have been pleased that many of the techniques used to examine ancient inscribed stones were useful in this twentieth-century American cemetery.

Nearly all the deceased had been born in the southwestern Macedonian town of Prilep, about forty miles northeast of the Greek frontier above Florina. Several stones appeared with death dates in the 1920s, and a few in the ‘teens. We halted at the edge of the cemetery, where the hillside had begun to collapse into a valley. I was told that the earliest gravestones had fallen away down the slope, and that the presence of snakes and ticks made the descent perilous. I was satisfied, for at my feet was an intact gravestone with the name of the deceased who had been born in “Prilep, Macedonia” in 1892, and who had died in Steelton in 1915. I was stunned. Here was clear evidence of a man who died in a central Pennsylvania mill town only two years after the Second Balkan War, and was identified at his burial as a Macedonian.4

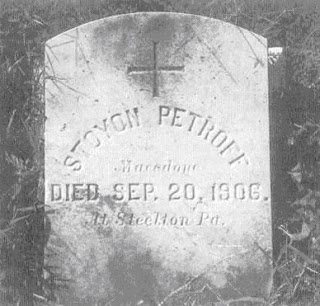

A subsequent trip to the cemetery in 1995 confirmed and enlarged the data base. I now have 30 gravestones in my photo file, the most interesting one of which was discovered in my 1995 visit. It is a simple, weather-worn headstone with the name of the deceased followed by (in English) “Mace-done [sic] died Sep. 20, 1906 At Steelton Pa.”5 Thus, six years before the First Balkan War in which the region of Macedonia was detached from the Ottoman Empire by Serb, Greek, and Bulgarian armies, the reality of Macedonia/Macedonian already existed among Macedonian immigrants in central Pennsylvania.

All of which is confirmed by reference to the 1920 United States census report from Steelton.6 The census-taker collected data from about 250 persons who lived along Main Street in Steelton. Of the total 76 claimed to have been born in “Macedonia,” and to have “Macedonian” as their mother tongue.7 All 76 listed their parents as having been born in “Macedonia,” With “Macedonian” as their mother tongue. Thus 228 persons were identified by a U.S. census taker in 1920 on a single street in Steelton as having a Macedonian connection.

In the second century B.C. the Romans ended the independence of the five-century-old kingdom of the Macedonians. During that period the Macedonians had emerged from the Balkan backwater to a prominence unanticipated and much heralded. Under the leadership of Philip II, the Macedonians conquered and organized the Greek city-states as a prelude to Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Persian Empire. Macedon continued to produce talented kings during the Hellenistic era, sufficient to threaten the new Roman order in the East, and perhaps even Italy itself.

The Macedonian kingdom was absorbed into the Roman Empire, never to recover its independence. During medieval and modem times, Macedonia was known as a Balkan region inhabited by ethnic Greeks, Albanians, Vlachs, Serbs, Bulgarians, Jews, and Turks. With the collapse of Ottoman rule in Europe in the early twentieth century, Greeks, Bulgarians, and Serbs fought for control of Macedonia, and when the final treaty arrangements were made in the 1920s, the Macedonian region had been absorbed into three modem states: Greece, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia. Despite population exchanges, ethnic minorities were preserved in all states, for example, Slavs and Turks in Greek Macedonia and Thrace, Albanians, Bulgarians, and Greeks in Yugoslav Macedonia, Greeks in Albania, and Greeks and Turks in southwestern Bulgaria (Pirin Macedonia). Thus, recent claims based on ethnic conformity and solidarity notwithstanding, the region of Macedonia has, until well into the twentieth century, housed Europe’s greatest multiethnic residue, giving its name to the mixed salad, “macédoine.”

Peaceful ethnic pluralism has not been a common feature of Balkan life, save under authoritarian regimes such as the Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires and Yugoslavia under Tito. Attempts to establish ethnic purity in the region have varied from simple legal and religious restrictions against cultural expression to outright violence, as in the case of the Bosnian “ethnic cleansing” campaign of the 1990s. In modern Greece the purification device is “Hellenization,” the absorption of non-Hellenes into the general Hellenic culture. In the forefront of the Hellenization movement has been the Orthodox Church, centered in the Greek partriarchate at Constantinople. 8 Its centuries-old effort to Hellenize the non-Hellenic Orthodox population of the Balkans was in keeping with the long-standing tradition of the Greek Church as the repository and protector of ancient Hellenism and Hellenic Christianity. Its success in this regard can be measured by the custom of the Turks, in their census reports, of identifying all Orthodox, without respect to ethnicity, as Greek, that is, adherents of the Church centered in Constantinople. With the growth of Serbian and Bulgarian nationalism, the Patriarchy unsuccessfully opposed the establishment of autonomous Serbian and Bulgarian churches in the nineteenth century, as it has the Macedonian church in the twentieth.

The emergence of a Macedonian nationality is an offshoot of the joint Macedonian and Bulgarian struggle against Hellenization. With the establishment of an independent Bulgarian state and church in the 1870s, however, the conflict took a new turn. Until this time the distinction between “Macedonian” and “Bulgarian” hardly existed beyond the dialect differences between standard “eastern” Bulgarian and that spoken in the region of Macedonia,9 and, while there had been disputes over which dialect should be the literary language, the arguments were subordinated to the greater struggle against Hellenization. By 1875, however, the first tracts appeared favoring a Macedonian nationality and language separate from standard Bulgarian,10 and the conflict had been transformed from an anti-Hellenization movement into a Bulgarian-Macedonian confrontation.

The region of Macedonia was freed from Turkish rule by the Balkan Wars (1912-13), and it was partitioned among Serbia (the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes in 1918, then Yugoslavia after 1929), Bulgaria, and Greece. Both Macedonian nationalism and a literary language continued to develop, despite the hostility of the three states that now laid claim to the region. 11 Serbs and Bulgarians continued to regard Macedonian as a dialect, not a real language, although, as Thomas Magner once pointed out, the decision about when a dialect becomes a language is sometimes a political, not a linguistic, act.12 The Greeks, under provisions of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920), were obligated to permit education and cultural outlets in native tongues for the minorities under Greek administration. Accordingly, a Macedonian grammar was produced in Athens in 1925,13 but never used because of an anti-Slav political climate in Greece in the late 1920s and 1930s, and Greek governments have prohibited the public and private use of Macedonian ever since.14

The development of a Macedonian ethnicity continued apace as an internal phenomenon, During World War II, the German forces occupying Yugoslavia exploited latent nationalist feelings, most infamously in organizing the fascist Ustashi group in Croatia. Less well known, however, is the German recognition of Macedonian nationalism. When the Allies persuaded Bulgaria to abandon the Axis in the autumn of 1944, the Germans were forced to reorganize the occupation of Macedonia—which hitherto had been under Bulgarian control—and to assume direct occupation themselves. German administration of Macedonia was short-lived, but the fact that Bulgarian postage stamps used in the area were overprinted "Macedonia" in Macedonian suggests that the Germans were consistent in their policy of encouraging local ethnicity in Macedonia, as they had in several other plaices in Europe.

Thus it is clear that Tito did not invent either a Macedonian ethnicity or a Macedonian language—as has been alleged—when he created a Macedonian Republic as a part of the postwar Yugoslav federal state. He rather provided legitimacy and support for a movement that had been under way- since at least the late nineteenth century. Whatever the merits and flaw of Tito's Yugoslavia, it was an experiment in ethnic diversity based on his recognition that the best hope for a unified South Slav state against traditional antagonists was to recognize and encourage ethnic development within the Yugoslav federal system. Tito's imprimatur on a Macedonian state was an attempt to counter traditional Bulgarian influence in the region of Macedonia, From the Yugoslav federal point of view, one of the best safeguards against the Bulgarians, who were traditional enemies of the Serbs, was to give recognition to the Macedonians as a separate south Slavic ethnicity. (As of this writing, the Bulgarians, like the Greeks, still do not recognize the Macedonians as a distinct nationality.) Tito's policy, was the culmination of a process that had been under way for the better part of a century; he provided legitimacy, for Macedonia and accelerated a natural passage of nation-building already well under way.

ROBERT R. KING, Minorities under Communism

An essay on modem political culture in a volume devoted to reciprocity in life and art in the ancient world may require a word or two of explanation. The theme of what follows is the modem rebirth of ancient Macedonia as a symbol of nationalism in a part of the Balkans that has been a killing ground in recent times. Many contemporary observers have attempted to reinvent the ancient history of the region in order to fit the necessities of their own lives and the vagaries of modem Balkan politics. It is a distorted reflection of the past, which, in its warped form, serves a purpose useful beyond the romantic antiquarianism of the classroom, the tourist path, and the museum. Midst the great body of Peter Green’s scholarship on literature, art, and the history of antiquity, one must not lose sight of the fact that he is one of our most perceptive observers of modem Greece, having lived among Greeks for several years, and having understood them better, perhaps, than they might have wished. Green’s essays in publications such as the New York Review, the New Republic, and the Times Literary Supplement are a rich source of insight for anyone who not only wishes to know something about contemporary Greece, but also requires some understanding of the issue of continuity and discontinuity between the past and present. 1 I hope that he will accept this essay in the spirit he has expressed in his own work on like subjects.

In the spring of 1993 I taught an undergraduate senior seminar to History majors, the topic of which was “Ethnic Minorities and the Rise of National States in the Modem Balkans.” We examined the status of minorities following the founding of Serbia (1815), Greece (1832), Bulgaria (1878), Albania (1913), and Yugoslavia (1918). Not long into the semester I asked my American students to identify their own ethnic backgrounds. One young woman said proudly that she was “Macedonian.” Grist for my mill. I asked her what that meant: was she Greek or Slav? She answered that she was Macedonian, and certainly not Greek, although she pointed out that she had spent most of her school life pretending that she was Greek, for, whenever her teachers asked about her ethnic background and she answered “Macedonian,” they responded, ”Oh, you must be Greek.” Now, as an honors student and a senior at a major university, she had stopped pretending she was Greek, and took my seminar in part to help her learn something about her Slavic Macedonian background.

Her family lived near a decaying central Pennsylvania mill town called, appropriately, Steelton. About halfway through the semester, the student told me that she had visited her church cemetery in Steelton, and that she had seen a number of gravestones on which the deceased had been identified as having been born in “Macedonia.” I asked what the dates of burial were, and she said “Oh, the 1950s.” “Not good enough,” I responded, ”Next time you visit, look for earlier dates,” knowing that by the 1950s it would not be unusual for birthplaces to be given as “Macedonia” in light of the federal status of Macedonia as a Yugoslav Republic. About two weeks later my student informed me that she had seen gravestones of the 1930s with the Macedonian identification. I jumped at the chance. “I’m going to pay you a visit in Steelton,” I told her. “Find some old-timer in your church, and let’s go looking for gravestones.”

Steelton is located along the Susquehanna River, just south of Harrisburg. The deteriorated mills, now largely deserted, stretch along the river, separated from a dilapidated old working-class community by a highway. Affluence has lured many people into the suburbs of Harrisburg a few miles away, and the houses and people who remain have clearly seen better times. The town climbs a bluff from the river. The higher parts are marked by greenery, better kept and larger homes, and bits of parkland. On the summit of one of the highest bluffs is an open, grassy area of several acres, the site of the Baldwin cemetery. Within lie the remains of immigrants who escaped the violence and poverty of Balkan life generations ago to seek economic well-being in the mills of Steelton.

The old woman who accompanied us knew the history of the cemetery and the churches whose members were buried there. One of the first things that struck me was that, by and large, the deceased who were identified as Serbs, Bulgarians, or Macedonians were buried in separate parts of the cemetery. In death, they sought the separation that sometimes eluded them in life. The old Macedonian woman had little but contempt for the Serbs, many of whom she had known, but she sometimes appeared confused by the distinctions between Macedonians and Bulgarians. For until the establishment of the Macedonian Autocephalous Orthodox Church in 1967, 2 the Macedonians belonged to either the Bulgarian Orthodox Church or to the “Macedonian-Bulgarian” Orthodox Church described on a few gravestones. Indeed, the Macedonian community in Steelton had apparently experienced internal division over whether their priests should most legitimately have been trained in Macedonia or in Bulgaria.

We picked our way past hundreds of gravestones, stopping to take photographs 3 and looking for earlier dates. Some stones were engraved in Latin letters, most in Cyrillic. A few decrepit headstones had been replaced with new ones, but most were original, and I mused that my old teachers of epigraphy would have been pleased that many of the techniques used to examine ancient inscribed stones were useful in this twentieth-century American cemetery.

Nearly all the deceased had been born in the southwestern Macedonian town of Prilep, about forty miles northeast of the Greek frontier above Florina. Several stones appeared with death dates in the 1920s, and a few in the ‘teens. We halted at the edge of the cemetery, where the hillside had begun to collapse into a valley. I was told that the earliest gravestones had fallen away down the slope, and that the presence of snakes and ticks made the descent perilous. I was satisfied, for at my feet was an intact gravestone with the name of the deceased who had been born in “Prilep, Macedonia” in 1892, and who had died in Steelton in 1915. I was stunned. Here was clear evidence of a man who died in a central Pennsylvania mill town only two years after the Second Balkan War, and was identified at his burial as a Macedonian.4

A subsequent trip to the cemetery in 1995 confirmed and enlarged the data base. I now have 30 gravestones in my photo file, the most interesting one of which was discovered in my 1995 visit. It is a simple, weather-worn headstone with the name of the deceased followed by (in English) “Mace-done [sic] died Sep. 20, 1906 At Steelton Pa.”5 Thus, six years before the First Balkan War in which the region of Macedonia was detached from the Ottoman Empire by Serb, Greek, and Bulgarian armies, the reality of Macedonia/Macedonian already existed among Macedonian immigrants in central Pennsylvania.

All of which is confirmed by reference to the 1920 United States census report from Steelton.6 The census-taker collected data from about 250 persons who lived along Main Street in Steelton. Of the total 76 claimed to have been born in “Macedonia,” and to have “Macedonian” as their mother tongue.7 All 76 listed their parents as having been born in “Macedonia,” With “Macedonian” as their mother tongue. Thus 228 persons were identified by a U.S. census taker in 1920 on a single street in Steelton as having a Macedonian connection.

In the second century B.C. the Romans ended the independence of the five-century-old kingdom of the Macedonians. During that period the Macedonians had emerged from the Balkan backwater to a prominence unanticipated and much heralded. Under the leadership of Philip II, the Macedonians conquered and organized the Greek city-states as a prelude to Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Persian Empire. Macedon continued to produce talented kings during the Hellenistic era, sufficient to threaten the new Roman order in the East, and perhaps even Italy itself.

The Macedonian kingdom was absorbed into the Roman Empire, never to recover its independence. During medieval and modem times, Macedonia was known as a Balkan region inhabited by ethnic Greeks, Albanians, Vlachs, Serbs, Bulgarians, Jews, and Turks. With the collapse of Ottoman rule in Europe in the early twentieth century, Greeks, Bulgarians, and Serbs fought for control of Macedonia, and when the final treaty arrangements were made in the 1920s, the Macedonian region had been absorbed into three modem states: Greece, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia. Despite population exchanges, ethnic minorities were preserved in all states, for example, Slavs and Turks in Greek Macedonia and Thrace, Albanians, Bulgarians, and Greeks in Yugoslav Macedonia, Greeks in Albania, and Greeks and Turks in southwestern Bulgaria (Pirin Macedonia). Thus, recent claims based on ethnic conformity and solidarity notwithstanding, the region of Macedonia has, until well into the twentieth century, housed Europe’s greatest multiethnic residue, giving its name to the mixed salad, “macédoine.”

Peaceful ethnic pluralism has not been a common feature of Balkan life, save under authoritarian regimes such as the Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires and Yugoslavia under Tito. Attempts to establish ethnic purity in the region have varied from simple legal and religious restrictions against cultural expression to outright violence, as in the case of the Bosnian “ethnic cleansing” campaign of the 1990s. In modern Greece the purification device is “Hellenization,” the absorption of non-Hellenes into the general Hellenic culture. In the forefront of the Hellenization movement has been the Orthodox Church, centered in the Greek partriarchate at Constantinople. 8 Its centuries-old effort to Hellenize the non-Hellenic Orthodox population of the Balkans was in keeping with the long-standing tradition of the Greek Church as the repository and protector of ancient Hellenism and Hellenic Christianity. Its success in this regard can be measured by the custom of the Turks, in their census reports, of identifying all Orthodox, without respect to ethnicity, as Greek, that is, adherents of the Church centered in Constantinople. With the growth of Serbian and Bulgarian nationalism, the Patriarchy unsuccessfully opposed the establishment of autonomous Serbian and Bulgarian churches in the nineteenth century, as it has the Macedonian church in the twentieth.

The emergence of a Macedonian nationality is an offshoot of the joint Macedonian and Bulgarian struggle against Hellenization. With the establishment of an independent Bulgarian state and church in the 1870s, however, the conflict took a new turn. Until this time the distinction between “Macedonian” and “Bulgarian” hardly existed beyond the dialect differences between standard “eastern” Bulgarian and that spoken in the region of Macedonia,9 and, while there had been disputes over which dialect should be the literary language, the arguments were subordinated to the greater struggle against Hellenization. By 1875, however, the first tracts appeared favoring a Macedonian nationality and language separate from standard Bulgarian,10 and the conflict had been transformed from an anti-Hellenization movement into a Bulgarian-Macedonian confrontation.

The region of Macedonia was freed from Turkish rule by the Balkan Wars (1912-13), and it was partitioned among Serbia (the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes in 1918, then Yugoslavia after 1929), Bulgaria, and Greece. Both Macedonian nationalism and a literary language continued to develop, despite the hostility of the three states that now laid claim to the region. 11 Serbs and Bulgarians continued to regard Macedonian as a dialect, not a real language, although, as Thomas Magner once pointed out, the decision about when a dialect becomes a language is sometimes a political, not a linguistic, act.12 The Greeks, under provisions of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920), were obligated to permit education and cultural outlets in native tongues for the minorities under Greek administration. Accordingly, a Macedonian grammar was produced in Athens in 1925,13 but never used because of an anti-Slav political climate in Greece in the late 1920s and 1930s, and Greek governments have prohibited the public and private use of Macedonian ever since.14

The development of a Macedonian ethnicity continued apace as an internal phenomenon, During World War II, the German forces occupying Yugoslavia exploited latent nationalist feelings, most infamously in organizing the fascist Ustashi group in Croatia. Less well known, however, is the German recognition of Macedonian nationalism. When the Allies persuaded Bulgaria to abandon the Axis in the autumn of 1944, the Germans were forced to reorganize the occupation of Macedonia—which hitherto had been under Bulgarian control—and to assume direct occupation themselves. German administration of Macedonia was short-lived, but the fact that Bulgarian postage stamps used in the area were overprinted "Macedonia" in Macedonian suggests that the Germans were consistent in their policy of encouraging local ethnicity in Macedonia, as they had in several other plaices in Europe.

Thus it is clear that Tito did not invent either a Macedonian ethnicity or a Macedonian language—as has been alleged—when he created a Macedonian Republic as a part of the postwar Yugoslav federal state. He rather provided legitimacy and support for a movement that had been under way- since at least the late nineteenth century. Whatever the merits and flaw of Tito's Yugoslavia, it was an experiment in ethnic diversity based on his recognition that the best hope for a unified South Slav state against traditional antagonists was to recognize and encourage ethnic development within the Yugoslav federal system. Tito's imprimatur on a Macedonian state was an attempt to counter traditional Bulgarian influence in the region of Macedonia, From the Yugoslav federal point of view, one of the best safeguards against the Bulgarians, who were traditional enemies of the Serbs, was to give recognition to the Macedonians as a separate south Slavic ethnicity. (As of this writing, the Bulgarians, like the Greeks, still do not recognize the Macedonians as a distinct nationality.) Tito's policy, was the culmination of a process that had been under way for the better part of a century; he provided legitimacy, for Macedonia and accelerated a natural passage of nation-building already well under way.

Which modern state has the most legitimate claim to the territory of the ancient Macedonian kingdom? All and none. If the claim is purely geographical, Greece, Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia have equal claims on the land of the ancient Macedonians now living within the boundaries of these respective national states. That is, the regions south of Skopje in the Republic of Macedonia, around Thessaloniki in Greece, and around Blagoevgrad in southwestern Bulgaria, are equally situated within the land of Ancient Macedonia, and the residents of all three areas can claim legitimacy based on present occupancy.

If the claim is based on ethnicity, it is an issue of a different order. Modern Slavs, both Bulgarians and Macedonians, cannot establish a link with antiquity, as the Slavs entered the Balkans centuries after the demise of the ancient Macedonian kingdom. Only the most radical Slavic factions—mostly émigrés in the United States, Canada, and Australia—even attempt to establish a connection to antiquity. For contemporaty Greeks, however, it is a different matter, as it is an article of faith among most of them that the Ancient Macedonians were Greek, and that noone but modern Greeks may claim right to the name and culture of the Ancient Macedonians. 17 No matter that genetic purity in the Balkans is a fantasy, or that there is no such thing as a cultural continuity in the Macedonian region from antiquity to the present. Politics in the Balkans transcends historical and biological truths. [p 255]

The propaganda campaign in Greece has been forceful. And one need not look to Greek governments as the source of the propaganda; the feelings are widespread and deeply felt. There are sufficient private political, cultural, and academic societies to formulate and maintain anti-Macedonian sentiments.18 In 1992, my students and I boarded an Olympic airplane in Santorini for the flight to Athens. Pasted to the exterior of the fuselage next to the rear door through which we entered was a printed Olympic Aviation pilots' union sticker that read "MACEDONIA IS GREEK. Always was, Always will be. STUDY HISTORY!" in English. During the short flight to Athens, the cabin attendants passed out copies of the sticker to the passengers, most of whom were foreign tourists. The phrases "Macedonia. 4000 years [sic] of Greek history" and "Macedonia is Greek" became a feature of ordinary Greek life, forming postmarks on letters processed in the mail system, and even adorning the paper table mats distributed by an Athenian wine company to Greek restaurants in the United States. Telephone cards now widely used throughout Greece bear the inscription "Macedonia is one and only and it is Greek," in Greek and English, despite the fact that for most of the 2,600 years since the genesis of the ancient Macedonian kingdom ethnic Greeks have been a minority of the population. The overwhelming Hellenic impact on Greek Macedonia is largely the result of the settlements and population exchanges of the early 1920s. Even Thessaloniki, with its rich Byzantine architectural heritage, counted far fewer Greeks than either Sephardic Jews or Turks until after the Balkan Wars of 1912-13.

Rumor was rife in Athens that the paper currency of the Republic of Macedonia featured the White Tower of Thessaloniki, a monument that, although probably Turkish in origin, had come to symbolize the city since its incorporation into the Greek state in 1912. In fact, no monument that has at any time been within the boundaries of the Greek state appears on any Macedonian currency. The currency designs consist mainly of medieval churches, fortifications, and quaint village scenes.19 And until recently, many persons in Athens believed the false rumor that the airport in Skopje had been named after Alexander the Great.

Nowhere is the battle fought more fiercely than among Greek and Macedonian émigré communities in Australia, Canada, and the United States.20 Some of the energy in this conflict results from the passion of post-World War II immigrants from Macedonia who introduced a more intense anti-Bulgarian nationalism than had existed among the older generations of émigrés, some of whom still had some pro-Bulgarian feelings dating from the early twentieth century. Some of the conflict was generated by Greek immigrants reacting against the writings and demonstrations of the Macedonians, often exacerbated by the residue of hatreds generated by the Greek Civil War. And certainly the fervency and frequency of clashes among émigrés can be explained by the simple fact that they were freer to express their political views in their newly adopted Western democracies than they had been in their Balkan homelands. Such is the concentration of feeling among the émigrés that it is difficult to know whether they are being driven by governments in Athens and Skopje or are the driving force themselves. Among Greek and Macedonian émigrés, much of the hostility is directed toward one another, but there is another, more subtle, campaign designed to influence public opinion in the English-speaking world.

Among the opening rounds fired in the struggle for public opinion was an exhibition of antiquities that included recently excavated materials from the ancient Macedonian royal burials at Vergina in northern Greece. Opening in Washington in 1980, the exhibition and its offshoots toured a number of U.S., Canadian, and Australian cities during the next two years, under the title "The Search for Alexander." While undeniably a lavish display of rich and beautiful objects as well as a tribute to the skills of Greek

archaeologists whose efforts produced the materials, the exhibition—forwhich the Greek government amended its own antiquities law in order to permit these items from the national heritage to travel abroad—was widely seen as a device to link modern Greece with ancient Macedonia.21 The Macedonian community responded by establishing a chair in (Slavic) Macedonian Studies at the University of Melbourne, much to the outrage of the active Greek community in Australia.

In response, the Australian Institute of Macedonian Studies sponsored the First International Congress on Macedonian Studies, designed to "trace the Greek origins of the people who inhabited Macedonia from earliest antiquity through to modern times."22 It became clear to all concerned that many aspects of the Congress would become politicized, as the large Macedonian community in Melbourne was determined to disrupt the proceedings, which they believed were part of a "world-wide campaign organized by the Greek government" to deny the legitimacy and identity of the Macedonian people. For Melbourne is a hotbed of ill feeling between the Greek and Macedonian communities. There were shouting matches and occasional minor bloodshed in the streets.

In an effort to repair the damage done from a politicized 1988 conference, the Institute sponsored a second international congress in 1991, with its theme strictly confined to ancient Macedonia. Unlike the first congress, which was dominated by Greek speakers with a clear political agenda, the second was coordinated with faculty from the University of Melbourne, and a number of foreign scholars—including this author—were invited to participate. In general, the quality of papers, most of which were on "safe" subjects, was high. But Balkan political passions, always lying just beneath the surface, erupted as it became clear that both Greek and Macedonian émigrés and some scholars from Greece were unable to separate the past from the present. Analyses of the ancient Macedonians, however soundly based on impartial scholarship, that did not seem to support modern political views, were attacked, and at one point the Greek delegation from Thessaloniki refused to continue their participation in the scholarly sessions until a certain Western scholar apologized for having presented conclusions that appeared to them to be politically incorrect.

In 1989 (during which year, incidentally, a new exhibition of ancient Macedonian antiquities toured three Australian cities), the Pan-Macedonian Association, an umbrella organization of local Hellenic Macedonian cultural societies in the United States and Canada, produced a five-day symposium co-sponsored by Columbia University, "Macedonia: History, Culture, Art," a program of public lectures and seminars for high-school and college teachers on ancient, medieval, and modern Macedonia. Despite efforts by the Greek and American participants to avoid the most sensitive political issues, parts of the symposium were disrupted by Macedonian demonstrators from Toronto who had been denied an opportunity to present their point of view. In 1988, the Smithsonian Institution in cooperation with the Embassy of Yugoslavia presented a two-day symposium in Washington on the heritage and culture of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia. In 1990, the Smithsonian Associates presented a lecture series on the glories of Greece, with an emphasis on the Greek heritage in Macedonia.

Macedonian and Greek disputants, both private and governmentsponsored, have thus courted the international scholarly community to provide a dignified venue for the continuing struggle. It appears to lend to the conflict the legitimacy of the Academy: Columbia University, the University of Melbourne, the National Gallery of Art, the Smithsonian Institution. But each of these events was marked by behavior that could not be controlled, as extremists from one side or the other disrupted proceedings or—worse—the papers and discussion presented by representatives of the scholarly community failed to provide the analysis of the past so eagerly sought by the contending factions. Scholars neutral in the conflict and whose conclusions are based upon the rules of evidence are looked upon with scorn: Greeks and Macedonians do not want neutrality, they want support, and, failing to get it from those who possess legitimate scholarly credentials, they feel betrayed and become hostile.23

Many Greeks today on both official and popular levels are disappointed and bitter that the publicity given over to the Macedonian Question within Greece, much of it designed to influence foreign opinion, has had little effect. By 1994, most governments had recognized the new Macedonian state. Newspapers, geographers, cartographers, international postal authorities, and even beauty pageants throughout the world, like individual foreign governments, accepted the state as "Macedonia," although, even at the present writing, Greece continues to refer to it as FYROM (The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia). That is, the Greeks have not been successful in their efforts to persuade the rest of the world of their position.24 One Greek critic of the situation (see n. 25 below) has written with reference to German journalists visiting Greece: "They might have lent a more sympathetic ear to Greece's apprehensions and taken them more seriously had they not been greeted at every turn by the vast, shoddy industry that has been made out of the sacred names and symbols of Macedonia and the kings of the Macedonian dynasty purely for domestic consumption; had they not been peremptorily commanded by signs and leaflets at airports and stations to study Greek history, and dragged round museums and archaeological sites to be shown things they regarded as self-evident—with precisely the opposite effect from that which was intended."

Thus, whatever other reasons may account for the Greek failure, the style with which the Greek position was presented may have been a contributing factor. It was a negligence also to pay heed to the warning made in the 1920s by one of the greatest statesman in Greek history, when Eleftherios Venizelos warned that Europeans would not be moved by arguments about "Greek rights." The appropriate term is "Greek interests," a framework for persuasion that, if presented effectively, might help sway world opinion to the Greek side on matters of international concern.25 In fact, sentimental Greek rights, not Greek interests, have dominated the Greek position in the present dispute. There is a strong Greek "interests" case to be made for stability, the recognition of existing frontiers, protection against external pandering to irredentist notions among ethnic minorities within Greece, and economic cooperation in this part of the Balkans. But the Greeks have attempted mainly to appeal to "rights" based on the distant past, and in the doing so, have made claims about that past that have dubious scholarly foundations (although see n. 32).

This is a tale of two Balkan nation-states. One has a long, distinguished history based in part upon the fame of an ancient society and the heritage of Byzantine Christianity. Modern Greeks point with pride to the power and glory of their past. But there may be something else at work in the Greek mentality. Until the early nineteenth century, Greeks of the Diaspora had been prominent throughout Europe in diplomacy, commerce, and cultural affairs. The courts and counting houses employed or were managed by Greeks whose skills in these matters were legendary in Europe for centuries, and who had a telling influence on European life out of proportion to their small numbers. With the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence and the consequent establishment of the modern Hellenic state in the 1820s and 1830s, many of these talented Greeks joined the effort to build the new nation. But in so doing, Greek influence abroad waned.26 In time, the Greeks, who had once been prominent in antiquity, in Byzantine times, and in modern Europe found that they were now relegated to obscurity, dependent upon major European states to provide financial resources and military security against the Turks, struggling to maintain a cohesive government in a remote tip of the Balkans, and engaged in an internal conflict between an imported authoritarian monarchy and the liberal notion that the inventors of democracy should have progressive constitutional government. Thus emerged one of the enduring characteristics of modern Greek life: a desperate attempt to regain a past glory, rooted in the cultural accomplishments of antiquity and the religious and political might of Byzantium. An identification with the ancient Macedonians is part of that attempt.

On the other hand, the Macedonians are a newly emergent people in search of a past to help legitimize their precarious present as they attempt to establish their singular identity in a Slavic world dominated historically by Serbs and Bulgarians. One need understand only a single geopolitical fact: As one measures conflicting Serb and Bulgarian claims over the past nine centuries, they intersect in Macedonia. Macedonia is where the historical Serb thrust to the south and the historical thrust to the west meet. This is not to say that present Serb and Bulgarian ambitions will follow their historical antecedents. But this is the Balkans, where the past has precedence over the present and the future.

The twentieth-century development of a Macedonian ethnicity, and its recent evolution into independent statehood following the collapse of the Yugoslav state in 1991, has followed a rocky road. In order to survive the vicissitudes of Balkan history and politics, the Macedonians, who have had no history, need one. They reside in a territory once part of a famous ancient kingdom, which has borne the Macedonian name as a region ever since and was called ”Macedonia” for nearly half a century as part of Yugoslavia. And they speak a language now recognized by most linguists outside Bulgaria, Serbia, and Greece as a south Slavic language separate from Slovenian, Serbo-Croatian, and Bulgarian. Their own so-called Macedonian ethnicity had evolved for more than a century, and thus it seemed natural and appropriate for them to call the new nation “Macedonia” and to attempt to provide some cultural references to bolster ethnic survival. One of these cultural references was the 16-pointed sunburst that was a symbol of the ancient Macedonians, as known from recent archaeological discoveriesat the old Macedonian center of Aegae, near the Greek village of Vergina.27 The yellow sunburst became the centerpiece of the new red Macedonian national flag, and was featured on a postage stamp. It was perhaps no coincidence that in the spring of 1992, only a few months after the declaration of Macedonian independence, the Greek government released a 100-drachma coin that bore the same symbol.28 The sunburst appears on the arm patches of the uniforms of crowd-control police in Athens. It replaces the letter 0 in the logo of the Greek television network "Makedonia." It is the symbol of the Bank of Macedonia Thrace. It adorns some military vehicles on the streets of Athens, and is prominently displayed at the gates of an army camp at Litochoro below Mount Olympus. The Greek Parliament made the sunburst an official symbol of the Greek state, and the Great Sunburst War commenced, both sides claiming rights to the sunburst, with Greeks adamantly demanding that the Macedonians abandon their official use of the symbol. The conflict raged for three years, apparently ending in September 1995 when Macedonia agreed to relinquish the sunburst as a national symbol as part of negotiations designed to resolve a number of outstanding issues.

It is difficult to know whether an independent Macedonian state would have come into existence had Tito not recognized and supported the development of Macedonian ethnicity as part of his ethnically organized Yugoslavia. He did this as a counter to Bulgaria, which for centuries had a historical claim on the area as far west as Lake Ohrid and the present border of Albania. What Greeks seem not to have understood is that a viable small Macedonian state in the region where Bulgarians and Serbs have clashed in the past is perhaps the best security that Greeks could hope for along their northern border. Instead of encouraging the development of such a state, they have done virtually everything short of military action to thwart its continued existence. Common sense would dictate that a Greek-Macedonian alliance would be mutually beneficial. The Vardar-Axios river valley is the ancient historically significant route from the Aegean Sea to the inner Balkans. Close ties would benefit Thessaloniki, the outlet for such trade. Moreover, Macedonia is poor and economically undeveloped; it had remained the backwater of modern Yugoslavia, as anyone who traveled in the region before the breakup of Yugoslavia knows firsthand. The Greeks possess the Balkans' finest skills in banking, trade, and technology, much needed in Macedonia. Both nations would profit enormously from a sound economic and geopolitical link.29

It remains to be seen whether the Greeks will abandon their hostility to a neighboring state bearing the name of a famous ancient kingdom with which the Greeks claim kinship. Or whether the Macedonians will honor their pledge not to harbor irredentist notions or to intervene on behalf of the Macedonian minority in Greece.30 Or whether the Bulgarians will reassert their historic medieval claims on the region. Or whether the growing Albanian minority in Macedonia will continue to provoke repressive

measures on the part of the government in Skopje.31 It is, all told, a very Balkan problem, in a part of the world where many people prefer a past bent out of shape rather than a reasonable and peaceful vision of the future.32

NOTES

1. E.g., see the title essay in Peter Green's Shadow of the Parthenon (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1972).

2. See Hugh Poulton, Who Are the Macedonians? (Bloomington and Indianapolis,1995), 180-82. As of this writing, the Macedonian Orthodox Church has not been recognized by any other Orthodox hierarchy. The role of the church as a component of Macedonian nationhood is an interesting, if unresolved, matter.

3. I have a file of these photos. I gave copies of a few of them to an American colleague in Athens who is interested in Macedonian matters. He reported that he showed them to a Greek friend who denounced them as fakes.

4. There is little doubt in my mind that the toponym should be considered as a statement of the ethnicity of the deceased. This is confirmed by the preferred and common Macedonian "off," and "eff" endings to surnames (as against typically Bulgarian endings for those born in Bulgaria), and by the census reports which distinguish between the Macedonian and Bulgarian languages. Curiously, the gravestones

of Serbs do not provide a toponym of origin.

5. Linguistically, it is impossible to determine what is meant by Macedone, whether "Macedonian" or "Macedonia." What is clear is that in 1906 (!) the stonecutter attempted to identify the deceased either by the place of his birth or by an ethnic term, however misspelled.

6. For what follows I am indebted to Professor Joseph C. Flay, whose experience in handling the information imbedded in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century U.S. census reports has proved invaluable. Only a portion of the 1920 Steelton census is reviewed here, and I was unable to check the census and gravestones against the records of the local Macedonian Orthodox Church. Although much remains to be done, the evidence gathered thus far points clearly to the conclusions that follow.

7. All those born in Bulgaria listed "Bulgarian" as their mother tongue. "Croatian" was given by those born in "Hungary" (Austria-Hungary, i.e., the Hapsburg Empire), while "Servian" (the old form of "Serbian") was spoken by those born in "Servia" and "Slavonia." Among the other languages given are Slovenian, Russian, Yiddish, Magyar, and Polish.

8. Victor A. Friedman, "The Sociolinguistics of Literary Macedonian," International Journal of the Sociology of Language 52 (1985): 31-57. For a detailed case study describing how the non-Hellenic components of a population long resident in the Langadas Basin north of Thessaloniki acquired Hellenic ethnicity in only two generations, see Anastasia Karakasidou, Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990 (Chicago, 1997). So successful was the program of Hellenization among these villagers that many persons of Slavic and Turkish background came to believe that their newfound Greek ancestry stretched back to antiquity.

9. The confusion of the old woman in the Baldwin cemetery in the 1990s (supra) about her Bulgarian/Macedonian identity is not an isolated case, as is made clear in the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (Cambridge, Mass., 1980), 690.

10. The conflict is described in Friedman, "Sociolinguistics of Literary Macedonian," 34-35, with relevant bibliography.

11. Some sense of Bulgarian hostility to the notion of a Macedonian nationality separate from Bulgaria can be found at large in a 900-page volume of documents translated into English and produced by the Institute of History of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Macedonia: Documents and Material (Sofia, 1978), which is also a powerful anti-Serbian tract. The modern Greek position is laid out most forcefully and persuasively by a sound scholar, Evangelos Kofos, in The Macedonian Question: The Politics of Mutation (Thessaloniki, 1987); "National Heritage and National Identity in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Macedonia," European History Quarterly 19 (1989): 229-67; and The Impact of the Macedonian Question on Civil Conflict in Greece (1943-49) (Athens, 1989). The prize for Greek jingoism must surely go to Nicolaos K. Martis, The Falsification of Macedonian History (Athens, 984), now unfortunately in its fourth edition.

12. Thomas F. Magner, "Language and Nationalism in Yugoslavia," Canadian Slavic Studies 1 (1967): 346. Or, as Manning Nash once put it, a language is "a dialect with an army and a navy" (The Cauldron of Ethnicity in the Modern World [Chicago,1989], 6).

13. Friedman, "Sociolinguistics of Literary Macedonian," 49-50, and Poulton, Who Are the Macedonians? 88-89.

14. For a frightening report of Macedonian ethnicity-denial in contemporary Greece, written from the perspective of a cultural anthropologist of Hellenic background, see Anastasia Karakasidou, Politicizing Culture: Negating Ethnic Identity in Greek Macedonia,"Journal of Modem Greek Studies 11 (1993): 1-28. Karakasidou's article resulted in a storm of protest from Greece. Among the less extreme reactions were those of N. Zahariadis, B. C. Gounaris, and C. G. Hatzidimitriou, published as review essays in Balkan Studies 34 (1993): 301 - 51. To the credit of that Thessaloniki based journal, the editors gave Karakasidou the opportunity to respond to her critics: "National Ideologies, Histories, and Popular Consciousness: A Response to Three Critics," Balkan Studies 35 (1994): 113-46. In reviewing the debate, the impartial observer will note that the criticisms reveal a lack of understanding of Karakasidou's anthropological methods. One can hardly find a more instructive and revealing firsthand insight into the debate than these Balkan Studies essays.

Karakasidou's assessment is confirmed elsewhere. See, e.g., "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1990," a report submitted to the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, and the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, by the Department of State (February 1991), 1172-73, which raised strong protests from the Greek government and Hellenic Macedonian cultural societies in the United States; Denying Ethnic Identity: The Macedonians of Greece. Human Rights Watch/Helsinki (1994), and Poulton, Who Are the Macedonians ? 1 6 2 - 7 1 • And, following the declaration of Macedonian autonomy from the collapsing Yugoslav federation in 1991, Pope John Paul II include a brief statement in Macedonian as part of his traditional multilingual Christmas message. There were serious Greek protests over the pontiffs use of the "nonexistent Macedonian tongue." Certainly the early twentieth-century Macedonian immigrants in Steelton, Pennsylvania, believed that they were speaking a distinct language.

15. Poulton, Who Are the Macedonians? 116 - 21.

16. One such group, centered in Canada, believes that Linear B[!] is the ancient Macedonian language, from which Greek and all Slavic languages have derived, and that the ancient Thracians spoke Macedonian. Some of these beliefs find their way into print, e.g., G. Sotiroff, Kinks in the Linear B Script (Regina, Canada, 1969); id., "Homeric Overtones in Contemporary Macedonian Toponomy," Onomastica 41 (1971): 5-18; and id., "A Tentative Glossary of Thracian Words," Revue Canadienne

des Slavistes 8 (1963): 97-110.

17. No amount of reason will shake modern Greek faith in the Hellenic ethnicity of the ancient Macedonians and their kings. It is more than a political preference: many Greeks see it as a necessity, despite the inconclusive ancient evidence on the nationality of the Macedonians. But recent scholarship has begun to provide a response to old Greek arguments. There is an insufficient amount of evidence—the existence of Greek inscriptions in the kingdom of the Macedonians notwithstanding—to know what the native language or dialect was. E.g., several dialects of Greek were used in ancient Macedonia, but what was the Macedonian dialect? The evidence of ancient writers suggests that Greek and Macedonian were mutually unintelligible languages in the court of Alexander the Great. Moreover, if contemporary or historical opinion from antiquity means anything, the ancient world from the fourth century B.C. into the early Hellenistic period—roughly the age of Philip and Alexander—believed that the Greeks and Macedonians were different peoples. None of which, incidentally, denies that the Macedonians, at least in their court and gentry, were quite highly hellenized, as recent archaeology has clearly shown. See E. Badian, "Greeks and Macedonians," Macedonia and Greece in Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Times, Studies in the History of Art 10, ed. B. Barr-Sharrar and E. N. Borza (Washington, D.C., 1982), 33 - 51 ; Eugene N. Borza, In the Shadow of Olympus: The Emergence ofMacedon, rev. ed. (Princeton, 1992), ch. 4 and pp. 305-6; id., "Athenians, Macedonians, and the Origins of the Macedonian Royal House," in Studies in Attic Epigraphy, History, and Topography Presented to Eugene Vanderpool, Hesperia suppl. 19 (1982), 713; id., "Ethnicity and Cultural Policy at Alexander's Court," AncW23 (1992): 21-25; and id., "Greeks and Macedonians in the Age of Alexander: The Source Tradition," in Transitions to Empire: Essays in Greco-Roman History, 360-146 B.C. in Honor of E. Badian, ed. R. W. Wallace and E. M. Harris (Norman, Okla., 1996), 122-39. The most that one can hope for is that one's views of the ancient Macedonians will not be misinterpreted as taking sides in contemporary Balkan politics.

18. My own experience is that the Macedonian issue sometimes divides even families in Greece, so that, for the sake of domestic tranquility, discussion of the issue is prohibited. The only comparable forbidden topic that I know is the Greek Civil War.

19. The Moslem Albanian minority in Macedonia, which accounts for something over 20 percent of the population, has begun to protest Christian imagery on the official paper money of what purports to be a multicultural, multireligious nation.

20. For what follows, see the overview provided by Poulton, Who Are the Macedonians? 120-21, and by the keenest observer of the émigrés, Loring M. Danforth. The latter is an experienced cultural anthropologist working among Greeks and Macedonians, both natives and émigrés. Danforth's papers, including those presented at scholarly meetings and privately circulated, have won wide respect among Balkan experts. His earlier work has been enlarged and superseded by the publication of The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World (Princeton,1995), in which Danforth explores the character of Macedonian ethnicity both in the Balkans and among overseas émigrés. Some of what appears in this essay owes much to Danforth's work, which is fundamental to an understanding of the several complex issues that mark this subject.

21. In a speech of welcome given at the opening of the exhibition in Thessaloniki in July, 1980, the president of the Greek Republic, Constantine Karamanlis, said, "As for Greece, Alexander has served as no other man has done the dreams of the nation, as a symbol of indissoluble unity and continuity between ancient and modern Hellenism."

22. From the introduction to the volume of papers published from the conference, Macedonian Hellenism, ed. A. M. Tamis (Melbourne, 1990). In addition, much of what follows regarding the first two Macedonian Congresses is based on newspaper and eyewitness accounts. I was a participant in several of the Greek-sponsored symposia and conferences discussed in this section, and can testify to the credibility of what is written here. Of special value is the testimony of Danforth, Macedonian Conflict, whose fieldwork as an observer of émigré activity underlies his published scholarship.

23. Many of the papers presented at the second Melbourne congress, including one of my own on Alexander the Great, which caused an unfortunate uproar, were never published. A few papers from the working sessions, mainly by Australian scholars, eventually appeared in print; see Ancient Macedonia: An Australian Symposium. Papers of the Second International Congress of Macedonian Studies. The University of Melbourne, 8-13 July 1991, edited by Peter J. Connor, in Mediterranean Archaeology 7 (1994). Some in the Macedonian émigré community in North America have adopted Ernst Badian, Peter Green, and me as "their" scholarly authorities, believing (without basis) that we possess a pro-Macedonian bias in this conflict. While it is true that we share certain similarities in our views about the ancient Macedonians, none of us has, to the best of my knowledge, publicly expressed any political opinions on the modern Macedonian Question. Thus, in a recent telephone conversation initiated by a fervent Macedonian nationalist from Toronto who saw in me a potential ally, the caller expressed astonishment when I said that I thought his views on the languages of ancient and modern Macedonia were without scholarly merit and bordered on the absurd. He never called back.

24. For insight into one aspect of this failure, see Kyriakos D. Kentrotis, "The Macedonian Question as Presented in the German Press (1990-1994)," Balkan Studies 36.2 (1995): 319-26.

25. Ibid., 325.

26. Argued in detail by William H. McNeill, The Metamorphosis of Greece since World WarII (Chicago, 1978), 51-57.

27. The decorative sunburst symbol, found in Macedonian art and artifacts of the late classical and early Hellenistic eras, has been variously interpreted as a "royal" or "national" sign. While it may be impossible to distinguish between what was "royal" and what was "national" in the ancient Macedonian kingdom, the wide distribution of the symbol of the sunburst suggests a Macedonian tradition that may be associated with the origins of the royal house; see Hdt. 8.137-39 and Eugene N. Borza, "The Macedonian Royal Tombs: Some Cautionary Notes," Archaeological News 10 (1981): 81-82.

28. The first issues of these coins bore 1990 mint marks, but had been kept unreleased in storage until the changing political climate required their discharge into general circulation. The obverse of the coin bears a portrait of Alexander the Great. One further point about currency: until recently all Greek banknotes—50, 100, 500, 1,000, and 5,000-drachma notes—were watermarked with the head of the Charioteer of Delphi. The new 200-drachma and 10,000-drachma notes have as their watermark a portrait of Philip II of Macedon.

29. But the full recognition of Macedonia by Greece might raise other problems involving the Serbs; see Symeon A. Giannakos, "The Macedonian Question Reexamined: Implications for Balkan Security," Mediterranean Quarterly 3 (Summer1992): 26-47. This article is a balanced review of the various perspectives—Greek, Macedonian, Bulgarian, and Serbian—on the Macedonian Question in the immediate aftermath of the Yugoslav breakup.

30. One can hardly overemphasize the importance of this Macedonian minority in Greece, located primarily, but not exclusively in the area around Fiorina. Greece officially denies the existence of ethnic minorities within the country; see Hugh Poulton, The Balkans: Minorities and States in Conflict (London, I991), ch. 13, and Karakasidou, "Politicizing Culture" (cit. n. 14, above). In 1990, the president of the Greek Republic, Christos Sartzetakis, proclaimed: "In Greece there are only Greeks, of exclusively Greek descent, with the exception of the small minority which international treaties refer to as Muslim" (Athena Magazine [April 1990]: 256). The denial of the very existence of minorities in Greece is consistent with the centuriesold policy of hellenization, but it also denies the serious consequences of minority repression, especially when a neighboring state is dominated by a population of the same ethnicity. Greeks have supported the claims of repressed ethnic Greeks living in Albania since the formation of that state in 1913. Yet they deny the right of the government of Macedonia to support Macedonians living in Greece, and they do so by simply proclaiming that there are no Macedonians in Greece, only Slavicspeaking Greeks. Thus the Greeks actively promote the problem they fear most: foreign (Macedonian) support of a minority group in their own nation. See Stephanos Stavros, "The Legal Status of Minorities in Greece Today: The Adequacy of Their Protection in the Light of Current Human Rights Perceptions," Journal of Modern Greek Studies 13 (1995): 1-32, who argues that the treaty arrangements of the 1920s, ostensibly designed to protect the rights of minorities in Greece, are inadequate today, as Greek courts continue to issue decisions denying equal rights to some minorities.

31. In Macedonia, the main human rights issue relates to equal rights for its several ethnic minorities. Even though Macedonian law embodies the principle of equal rights for minorities, the practical application is uneven, especially with regard to employment and minority language education of ethnic Albanians, who number nearly 22 percent of the population. See A Threat to "Stability ": Human rights Violations in Macedonia, Human Rights Watch Report (New York, 1996).

32. Some things may be changing. In early 1996 the Greek government led by Prime Minister Costas Simitis and Foreign Minister Theodoros Pangalos adopted a policy of Balkans reconciliation in part as a response to increased tensions between Greeks and Turks. Pangalos was widely quoted in the Greek press and television as having stated (concerning the Republic of Macedonia), "[W]e spend too much time talking about Alexander the Great rather than addressing ourselves to the future of economic cooperation." There was the expected angry reaction from some quarters. In April 1996, the Serbian government formally recognized Macedonia as Macedonia. In Greece, the announcement was widely greeted with outrage and a sense of betrayal by what had been regarded as Greece's closest Balkans ally. Yet, within a few weeks Kathimerini, the most prestigious newspaper in Athens, published a 32-page supplement to its Sunday edition that was entirely devoted to an attractive description of the economic, social, and cultural life of Macedonia (although still called "Skopje"). This warming trend is consistent with travelers' reports that border crossings between Greece and Macedonia are routinely made without difficulty.

Comments

Post a Comment