This article was first published on 09 August 2021, on the site of Geopolitical futures (a US group of thinkers about geopolitics and future of nations).

Prospects for a ‘Mini-Schengen’ in the Balkans

The project is a

political response to the EU delaying membership talks.

By: Antonia Colibasanu

In July, the leaders of Serbia, North Macedonia and Albania

announced a new cooperation initiative for the region. Officially named the

Open Balkans project, and unofficially dubbed a mini-Schengen (named for the

European Union's much larger borderless travel area), it aims to lift

restrictions to travel and trade between the three countries by 2023. The

economic benefits will depend on how the project is implemented, but they’ll be

less important than its symbolic value. For the Western Balkans – that is,

Serbia, Albania, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro –

it’s the first serious political response to the European Union stalling

accession talks, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic began over a year ago.

Not all countries in the region have embraced the project,

however. Officials from Montenegro, Bosnia and Kosovo have said they see it as

unnecessary, underscoring the fact that divisions remain despite efforts toward

integration. Still, the leaders of the three countries involved seem to have

pegged Open Balkans as a likelier path to prosperity than EU membership at this

point. Either way, governments in the Western Balkans need to come up with

realistic solutions to their growing problems – and soon – to avoid a

reemergence of the conflicts and divisions that have long plagued the region.

Disillusionment With the EU

To understand the political significance of the Open Balkans

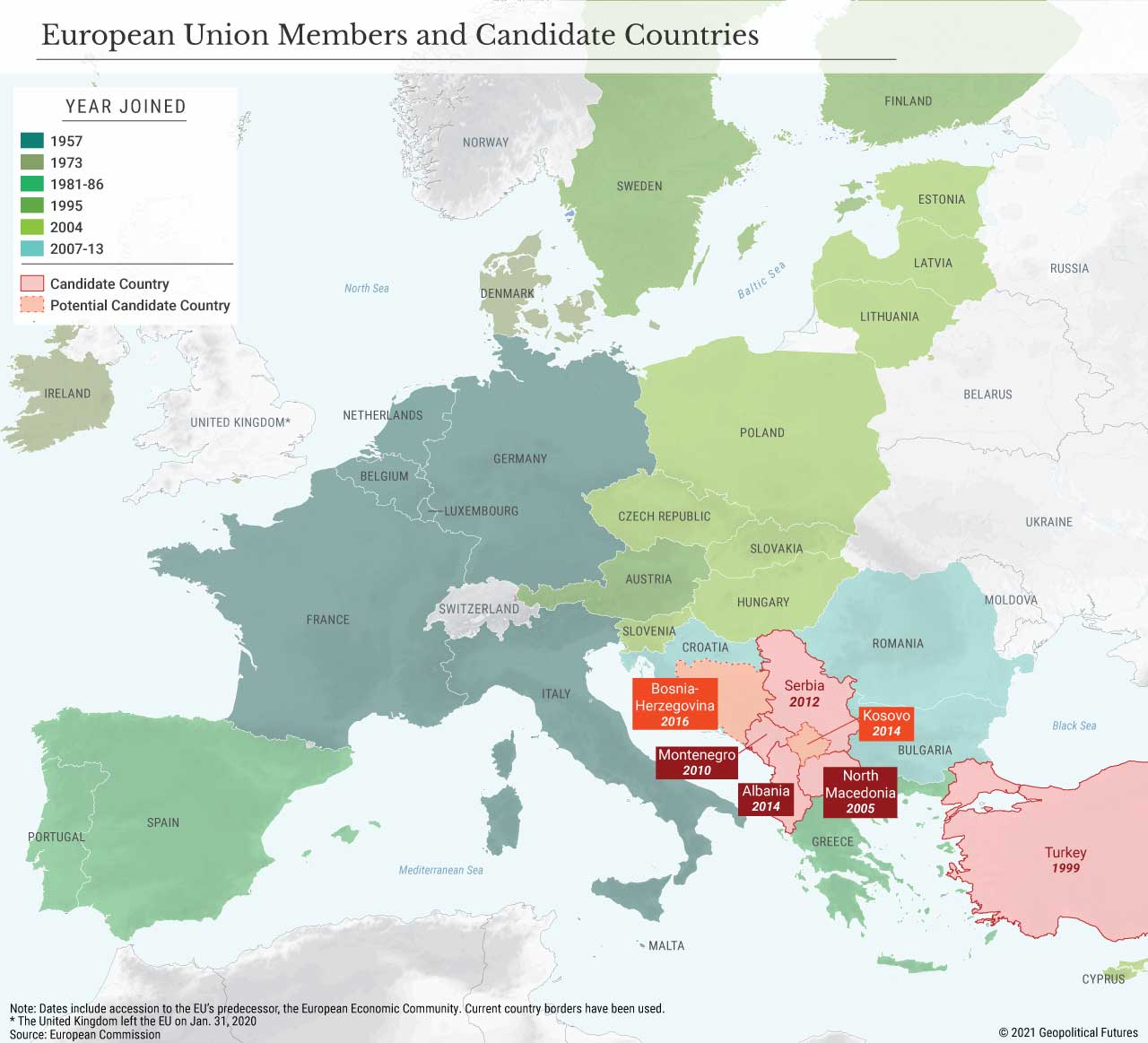

initiative, we first must understand the EU’s policy for the region. In 2020,

the European Commission announced a “revised enlargement methodology,” which

was supposed to increase transparency in the negotiation process for candidate

countries while also boosting monitoring of their readiness to join the bloc at

various steps in the process – which would allow member states to make a more

informed decision about whether the candidates should be accepted. Previously,

national leaders of member states voted on accession only after the European

Commission established, on its own, that all conditions for membership had been

met by the candidate country.

The move was presented at the time as a way to build trust

between member states and candidate states. It was triggered by the EU’s

internal challenges brought on by the 2008 economic crisis. As member states

faced their own growing structural problems, it was increasingly difficult to

reach consensus over strategic matters. Not only did the western and eastern

members not share the same interests, but they also didn’t share the same views

on democracy and rule of law. These differences, as well as the divide over how

to handle the refugee crisis, increased domestic opposition to the enlargement

process in some member states, with many believing that the EU needed to fix

itself before expanding membership eastward.

The new enlargement procedure was therefore sold as a way for

both the candidates and the member states to learn more about each other. In

reality, however, it was an extra burden complicating the negotiation process

with another layer of oversight and evaluation. It was also heavily

politicized, making it clear to candidate countries that the EU’s “enlargement

fatigue” was increasingly becoming a brick wall. This is particularly true for

Albania, North Macedonia, Serbia, Kosovo and Bosnia, countries that have yet to

enter formal talks with the EU on accession despite having submitted

applications for membership years ago.

In 2019, France blocked the opening of negotiations between the

EU and North Macedonia and Albania, saying that more reforms were needed from

the two countries before talks could start. The EU had previously promised to

open negotiations with North Macedonia once it settled its name dispute with

Greece – which it did in 2018, paving its way to joining NATO in 2020. The

Netherlands and Denmark joined France in vetoing Albania’s bid to open talks.

In 2020, Bulgaria blocked accession talks with North Macedonia,

refusing to approve the so-called negotiation framework, over a dispute about

historical links between the two countries. Bulgaria’s parliamentary elections

in 2021 surely played a role in its decision to stall the talks.

Since the new enlargement process was put in place, there has

also been little progress on the EU-sponsored talks to settle the long-standing

dispute between Kosovo and Serbia. Both agreed to participate in the dialogue

in hopes that it would boost their chances of joining the bloc. But following

parliamentary elections in February, Kosovo’s new prime minister has been

critical of the negotiations. With prospects for accession now dim, Pristina

seems to want to set a new agenda for talks, including putting Kosovo on equal

footing with Serbia. It seems EU accession is now a secondary consideration.

The new enlargement process, therefore, not only confirmed that

enlargement fatigue has truly set in but also forced the Western Balkans to

reconsider their positions on membership. The pressure on these countries has

been amplified by the pandemic. In 2020, economic growth in the Western Balkans

contracted by 3.4 percent – the region’s worst economic decline on record –

according to the World Bank. This situation requires these countries to find

and promote local solutions to their problems. Lifting barriers to regional

travel and business through the Open Balkans initiative may be one step in that

direction. It also shows the people of the Balkans that their political

leadership can make decisions without Brussels.

Socio-economic Factors

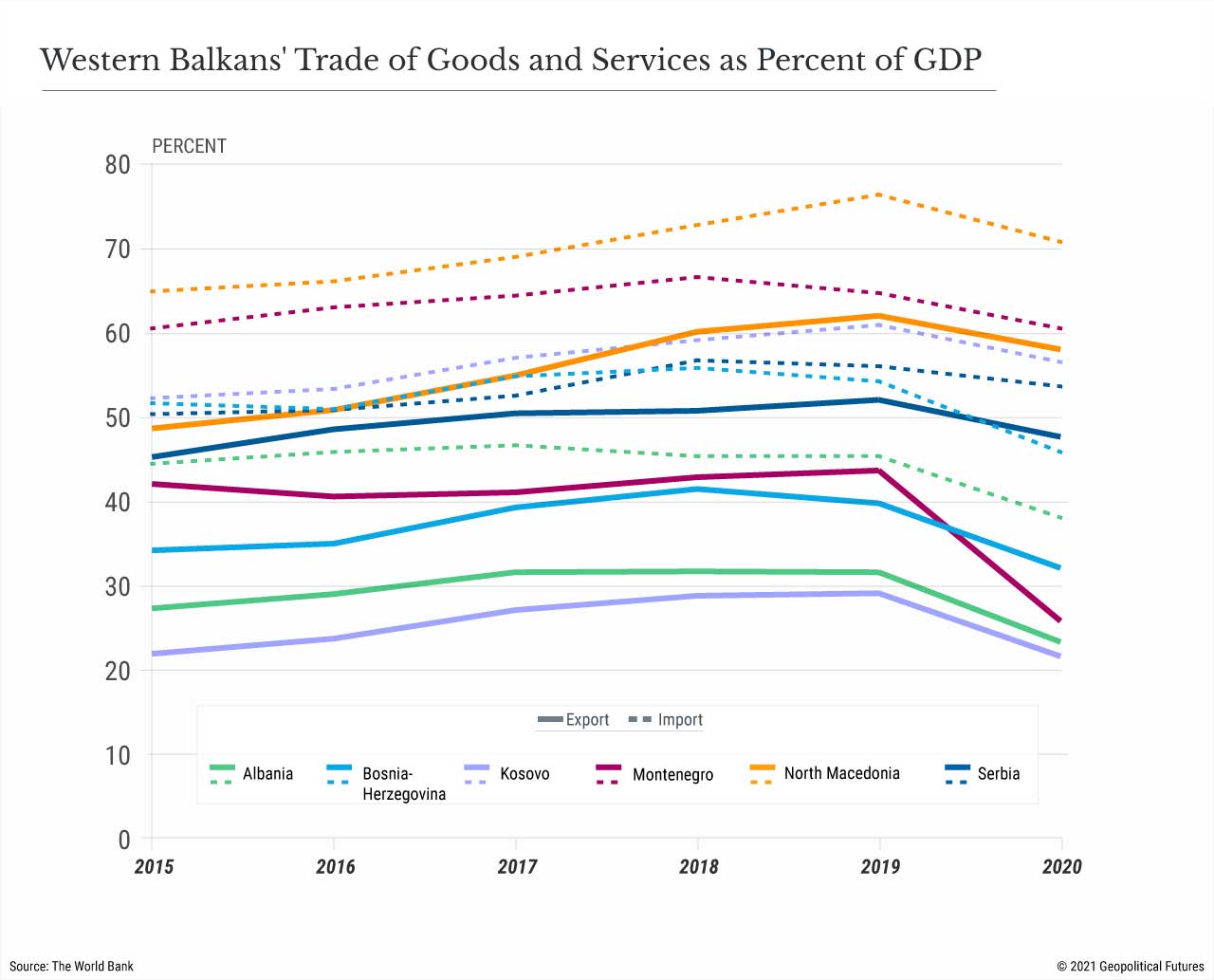

The pandemic has hit the economies of the Western Balkans

particularly hard in part because of their dependence on the service sector. In

Serbia, which has the most diversified economy in the region, the sector

accounts for 57 percent of employment. In Montenegro, which has a large tourism

industry, it employs more than 73 percent of workers. In Bosnia, services are

dominated by the public administration sector, which accounts for 9.5 percent

of gross domestic product and about 35 percent of total employment. In the

three remaining countries, trade, wholesale retail, tourism and transportation

dominate the services sector, employing almost half of the active populations

in each.

Since the pandemic, Montenegro has entered a deep recession,

while Kosovo saw its first economic contraction since it declared independence

in 2008, despite increases in government transfers and remittances from

Kosovars abroad. Bosnia’s economic growth has also slowed, leading to an increase

in unemployment. The effects on the labor market have highlighted the need to

address structural rigidities restraining growth in private sector jobs.

In North Macedonia, the economy entered its deepest recession

since independence. It was heavily affected by the decline in international

trade, which accounted for more than 60 percent of GDP pre-pandemic. Government

short-term support schemes helped cushion the impact, but considering the

prolonged global fallout, North Macedonia needs not only to continue structural

reforms that decrease its dependence on trade but also to invest more in

infrastructure in the long term.

The economy of Albania, which was hit by a massive earthquake in

2019, has stayed relatively stable due to pre-pandemic increases in public

spending, including hikes in government subsidies. It’s betting its recovery on

post-earthquake reconstruction efforts as well as hopes for increased domestic

consumption. The most resilient economy in the region has been Serbia, which

announced a stimulus package in February that it hopes will boost internal

demand.

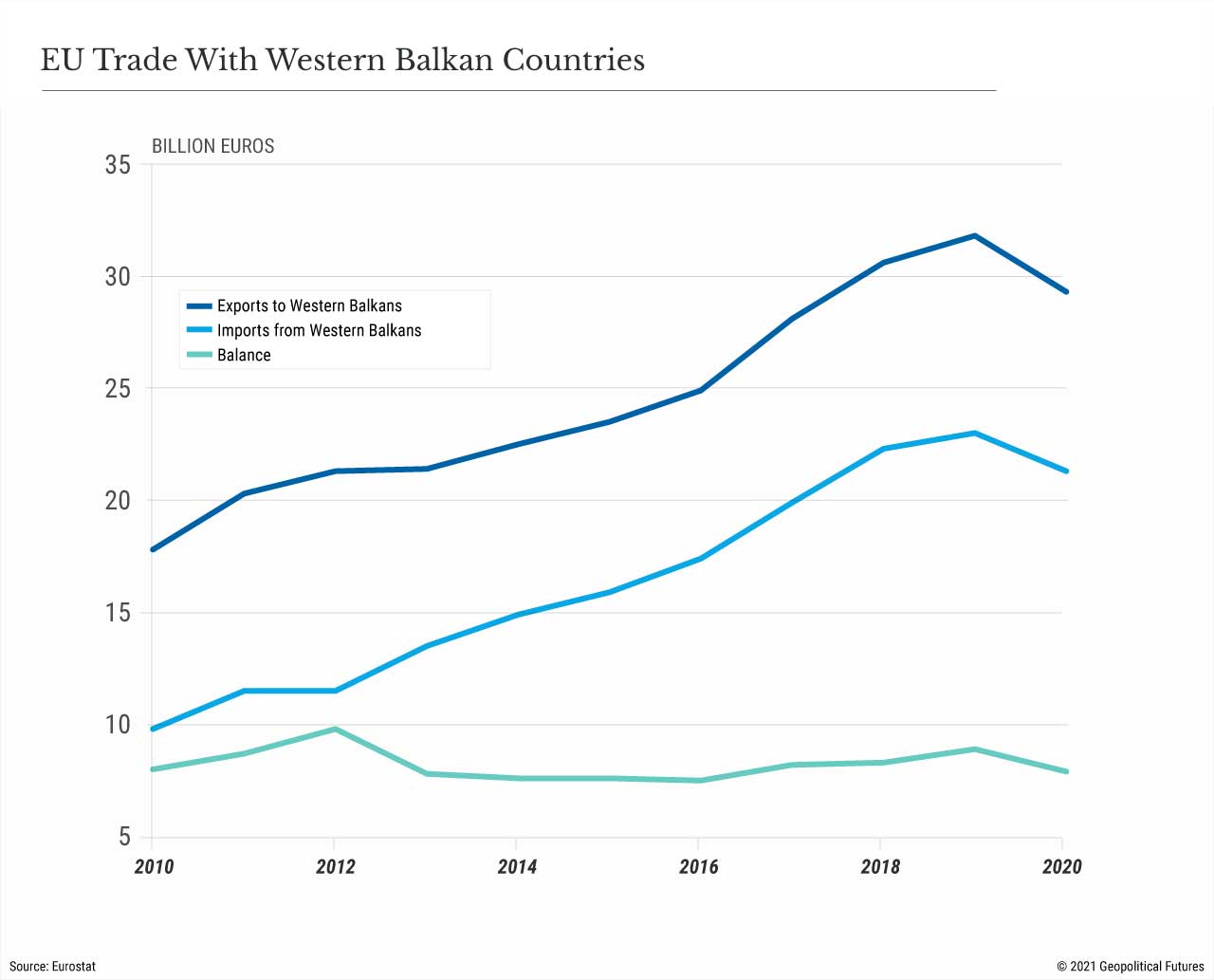

The crisis has highlighted a key vulnerability for these

economies: their dependency on external demand, either through tourism or trade

– both of which rely heavily on the EU. It’s easy to see, then, why EU

membership has been synonymous with economic development and stability for the

Balkans. While candidate countries receive some funding even before they open

accession negotiations, they will receive much if they are actually accepted

into the bloc. New members can expect development of large infrastructure

projects and growth in trade and investment in the first decade of membership,

all designed to build a foundation for stable economic growth.

The promise of peace through prosperity resonated for the people

of the Balkans, many of whom can barely depend on their paychecks to cover

their living costs. But as member states face structural economic problems of

their own, the prospect for prosperity even for those living within the EU are

growing dimmer.

In the past, Balkan states would balance between the EU and other

outside powers during turbulent economic times, eager to reap benefits from

anyone interested in gaining an advantage. Russia, China, the U.S. and even

Turkey have all offered support in times of need. But they’re now preoccupied

with internal problems. So, for the first time since the 1990s, the countries

of the Western Balkans are forced to find their own solutions to their

short-term problems. And realizing that EU accession is, at best, a long way

off, they also must confront deeper, long-term challenges that they’ve long

failed to address.

Tough Choices

It’s not the first time the Western Balkans has suffered from

its dependency on trade with the EU. The 2008 financial crisis hit the region

particularly hard and, notably, made the pain of EU enlargement fatigue more

acute. And so, as the crisis settled down, there began a behavioral shift over

EU membership. EU accession is still a stated goal for Balkan countries, but

its enthusiasm depends on how the public sees the advantages of joining. It’s a

painful process, one that is bearable only if the benefits are guaranteed.

Considering the challenges the EU has faced since 2010, the guarantees aren’t

exactly ironclad.

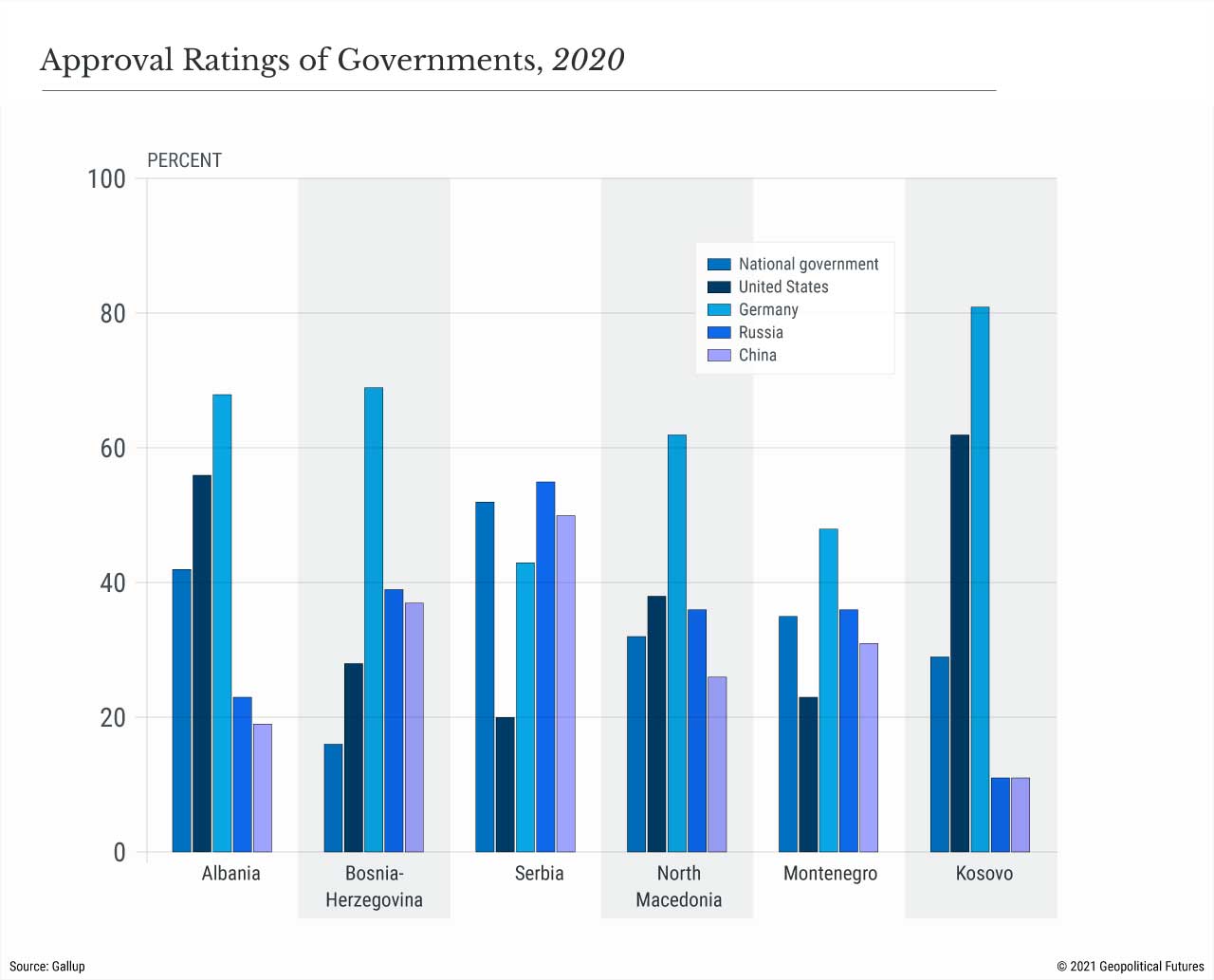

Typically, when the Balkans believe the EU can’t help, they turn

to other partners to fill the gap: Russia, China and the U.S. But the COVID-19

pandemic has forced all these countries to focus on their own problems. That,

in turn, affected how Balkan voters see their traditional benefactors. In other

words, public perception about the EU and other outside powers has slowly begun

to shift. According to Gallup’s World Poll, the approval rate for EU leadership

has fallen throughout the region (though it’s still north of 50 percent).

Interestingly, the U.S. enjoys growing approval rates in Serbia, while the

approval rates for Russia, Serbia’s traditional partner, have fallen. In

Kosovo, approval ratings for all outside powers – the U.S., China, Germany and

Russia – have dropped. These changes reflect developments in each country.

Serbia has been politically stable; Kosovo has not. In 2021, the latter elected

its first Kosovar anti-establishment party, which promised to focus on internal

challenges and enhance the country’s international posture.

In other places, changes were less visible. In Bosnia, for

example, the measures needed to manage the fallout from the pandemic require

political consensus. That’s impossible in an unstable political environment

such as Bosnia’s. In Montenegro, the fate of the country depends on how the

pandemic plays out, considering no structural change can be made in a few

months, and tourism remains the main source of income for most of the

population. (Not to mention that its public debt to China has increased

pressure on the government, which hopes to get the EU on its side to convince

Beijing to postpone repayment.) All this restrains the ability for both Bosnia

and Montenegro to announce any new strategic initiatives or even address

potential reforms.

In Albania, public approval rates for the EU have dropped

steadily over the past five years, even though they’re still above 70 percent.

The need to focus on reconstruction is not just an opportunity for the country

to maintain stability; it’s also the reason that public support for the

national government has increased. In North Macedonia, the refusal to open

negotiations after it changed its name and constitution was taken as a broken

promise. Trust in the EU's promises and approval rates have decreased since

2017. As the country needs to restructure its economy, the government is

focusing on showing what it can do on its own, without Brussels’ help or

direction.

This points to a larger regionwide trend of publics increasingly

demanding that their local leaders take action and rebuild the economy. Finding

solutions for the current problems hitting the already fragile economies isn’t

easy, but the governments are trying. In the case of Albania, North Macedonia

and Serbia, the establishment of the Open Balkans initiative, which promises

better regional cooperation, reflects the public's growing distrust in the EU

and the promise of a homegrown solution. Montenegro, which needs Brussels on

its side when talking to China, can't afford to join the initiative. Bosnia

doesn’t have the political stability to think about joining it. The new

government in Kosovo needs to stick to its campaign promises of not abandoning

the EU project – and to make sure it doesn’t “give in” to Serbia. (Joining the

Open Balkans initiative could certainly be seen as doing so.)

As EU prospects are no longer realistic, it becomes increasingly

complicated for the Western Balkans to work together toward a common goal. The

EU, or at least the prospect of EU membership, kept them together. But the

region is inclined to fragmentation. In geopolitics, 30 years isn’t a long

time. The generation that lived in Yugoslavia and participated in the bloody

conflicts of the 1990s is still alive. Some are nostalgic for their lives

before the war; others remember only the pain of war.

For this region to be stable, the population needs hope for a

better life, which includes a functioning labor market and economic growth. The

hope the EU provided was delusional; hope provided by local, national

authorities needs to be realistic. Otherwise, tensions will resurface,

affecting the stability of the region and that of Europe. When the EU couldn’t

provide much, these countries would look for help elsewhere, to find an

interested party ready to support them. The pandemic made it so that everyone

needed to focus internally, at least in the short term. The Western Balkan

states need to do the same.

Comments

Post a Comment